CIMRM Supplement - Prehistoric axe-head engraved with tauroctony and gigantomachy. Argos, Greece.

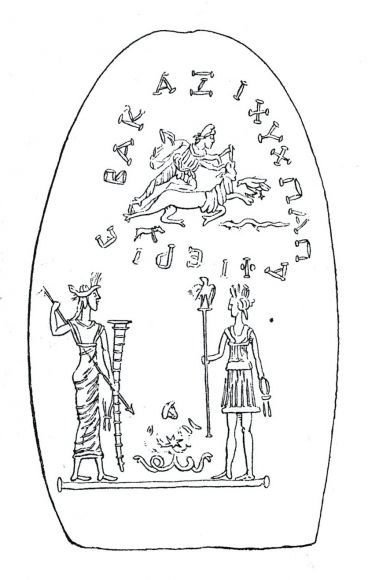

A second large axe-head now in Athens is said to come from Argos. It is of green color (serpentine) and slightly shorter than the Ephesian specimen (10.3 × 5.2). One side was engraved in Roman times with two scenes (Fig. 2).[28]

In the lower half we see the standing figures of Athena and Zeus in a scene familiar from a gigantomachy like the one on the Altar of Zeus at Pergamon: the goddess is about to stab a tiny snake-footed “giant” with her spear, while her father looks on holding a scepter topped by an eagle, his usual attribute. There are, however, some eastern features: Zeus grasps a wilted ankh-sign in his left hand and Athena holds or supports with her left hand a tall ribbed rhyton.[29]

In the upper register we find a simplified version of the well-known Mithraic icon: the god kneels on the back of the bull and stabs it, while three animals surround it from below. This second scene is encircled by two magical words: βακαζιχυχ and παπαφειρις. The first often appears alone on gemstones and translates the Egyptian phrase “son (or “soul”) of darkness”, even though it paradoxically is used often to describe solar deities, here presumably Mithras.30 The second word has yet to be fully deciphered.31

The parallelism between the two scenes on this axe-head is noteworthy: in both powerful gods (Mithras and Athena) threaten or stab powerful adversaries (a bull and a snake-footed “giant”). Because this object is unique, it is difficult to say what it was used for, but the parallel scenes of divine triumph and the magical inscriptions both suggest that it was a protective amulet.32 The orientation of the design, as we can see in Figure 2, suggests that the axe-head was positioned with its cutting edge pointing downwards, that is, in the opposite direction of the Ephesian stone. The back of this axe-head is uninscribed.

28 Figure 2 is after Cook (1925), p. 512, fig. 390. Below I follow the interpretation of Delatte (1914), p. 8–9 and Mastrocinque (1998), p. 25–27.

29 It is an Egyptian rhyton according to Delatte (1914), p. 8–9 and Mastrocinque (1998), p. 26–27. Harrison (1927), p. 57 apparently interpreted the lower scene as some kind of Mithraic initiation: “a figure that looks like a Roman soldier bearing a rod surmounted by an eagle is received by a priest: the soldier is probably qualifying to become an ‘Eagle’.” In the drawing that accompanies her discussion, the snake-footed giant is invisible.

Christopher A. Faraone, "Inscribed Greek Thunderstones as House- and Body-Amulets in Roman Imperial Times", Kernos 27 (2014), 257-284

| Tweet |