A couple of days ago, I happened to see a brand new anti-Catholic slur online on Instagram. Here’s the item:

It’s not spread that far as yet, but claims to be from Cracked.com – a US humour site.

The poster makes three claims:

The Catholic Church opposed street lights.

In 1831, Pope Gregory XVI even banned gas lighting in papal states.

The church argued that God very clearly established the delineation between night and day, and putting lights up after sundown flew in the face of God’s law.

Well that’s pretty plain. The Catholic Church under Gregory XVI made it offical teaching that street lights were evil, and that even (note the emphasis) gas lighting was banned in “papal states” (by which most people will understand “Catholic countries”).

It’s obvious that this poster is intended to defame, to injure and to bring contempt on the Roman Catholic Church. But it is interesting to find that the words in the poster are very recent indeed. In fact I can only find a single near-match anywhere. This is in a 2015 publication by Bruce H. Joffe, “My Name Is Heretic: Reforming the Church, from Guts to Glory”.[1] The author appears in fact to be a homosexual activist.[2] The Cracked.com poster is clearly derived (with a couple of word changes) from this.

The claim that “The church argued that God very clearly established the delineation between night and day, and putting lights up after sundown flew in the face of God’s law” does not appear elsewhere, and in the absence of evidence and reference we may hypothesise that Joffe simply invented it.

The poster also gives a reference, to Desmond Bowen.[3] But when we search for street lighting, we find only a single result:

Papal ceremonies assumed unprecedented magnificence, and audiences were conducted with more than royal protocol. The building programme of Leo XII was continued, more ancient churches and monuments were restored, new palaces were built, and the Vatican was further enriched with valuable collections of art. At the same time the people of Rome were denied street lighting, and the pope refused to allow the coming of the railway to the city. Gregory XVI was a thoroughgoing reactionary, but his policies were implemented only because of the presence of French and Austrian as well as papal troops.

The Google books preview indicates no other reference to street lighting in the book.

With every historical claim, our first step must be to discover whether the claim is in fact true, as stated. If it is true, we must next discover whether it is a fair representation of the facts, or a distortion.

Our first source of information is none other than the great Charles Dickens, in Bentley’s Miscellany, vol. 24, 1848, p.305, where he is reviewing a book about Italy by a certain James Whiteside, of whom more in a minute.

The effete but jealous despotism of the ancient system [of Papal government before Pope Pius IX] is well illustrated by the following anecdote.

“I became acquainted with a young, handsome, fashionable Count, who mixed largely in English society in Rome. During an evening’s conversation he remarked, he had never beheld the sea, and had a great desire to do so. I observed that was very easy, the sea was but a few miles distant, and if he preferred a sea-port, Civita Vecchia was not very far off. The Count laughed. ‘I made an effort to accomplish it, but failed,’ he then said. ‘ You English who travel over the world do not know our system. I applied lately for a passport to visit the coast; they inquired in the office my age, and with whom I lived; I said with my mother. A certificate from my mother was demanded, verifying the truth of my statement. I brought it; the passport was still refused. I was asked who was my parish priest; having answered, a certificate from him was required, as to the propriety of my being allowed to leave Rome. I got the priest’s certificate ; they then told me in the office I was very persevering, that really they saw no necessity nor reason for my roaming about the country just then, and that it was better for me to remain at home with my mother.’ He then muttered. ‘The priests, the priests, what a government is theirs !’”

This passage sufficiently explains Pope Gregory’s hostility to railroads, but the cause of his hostility to gas-lights is less generally known, and must not be suppressed. When the chairman of a company formed for lighting Rome with gas, waited on the Pope to obtain the required permission, Gregory indignantly asked how he presumed to desire a thing so utterly subversive of religion! The astonished speculator humbly stated that he could not see the most remote connection between religion and carburetted hydrogen. “Yes, but there is, sir,” shouted the Pope, “my pious subjects are in the habit of vowing candles to be burned before the shrines of saints, the glimmering candles would soon be rendered ridiculous by the contrast of the glaring gas-lights, and thus a custom so essential to everlasting salvation would fall into general contempt, if not total disuse.” No reply could be made to this edifying argument. Silenced, if not convinced, the speculator withdrew; the votive candles still flicker, though not so numerously as heretofore, and they just render visible the dirt and darkness to which Rome is consigned at night.

We need not spend too long on this anecdote, which Dickens – no friend of the church – tells us that he heard from a failed salesman. The aged and suspicious Pope doubtless had seen a series of such salesmen, and might well have said something sarcastic and irrefutable to get rid of a particularly irksome commercial gentleman. But sadly the veracity of salesmen cannot always be relied on, even when the sale succeeds.

Much more interesting is Whiteside’s anecdote about the Roman prince denied a passport. This gives an interesting picture of the Papal administration in the period – positively third-world. It’s the sort of story that might come out of Egypt today, or some African slum state, where ordinary people are knotted up in pointless and destructive bureaucracy. In this case no doubt the official really just wanted a bribe.

This gives us our first clues about this story. We are not, in fact, dealing with “the Catholic Church”. We are dealing with a now long-vanished petty Italian princedom, the Papal States, and its wretched and backward administration.

This is promptly confirmed when we consult Whiteside’s volume.[4] Unlike Dickens, who knew without saying why the Papal government had banned railways, Whiteside actually does know:

Political fears deterred the government from sanctioning railways. When Gregory understood his loving subjects of Bologna might visit him in Rome en masse, he would not hear of the innovation. I remember the remark of a man of business on the subject: “Il Papa non ama le strode ferrate.” No reasons were given for the refusal to adopt the improvement, except that his Holiness hated railways. Gregory reasoned as did an inveterate Tory of my acquaintance, who condemned railways because they were a vile Whig invention. Any improvements in agriculture which could be effected by agricultural societies were interdicted, all such noxious institutions repressed.

In fact if we read Whiteside’s pages, we see the familiar picture of a weak government, of the kind found everywhere in Africa today, suspicious of everything and willing to ban anything unless they see pecuniary advantage in it.

Around the same time, an Irishman named Mahoney published, under the pen-name of Don Jeremy Savonarola (!), a series of letters that he wrote from Italy.[5] These throw considerable light on attitudes in Rome at the time, not only among the government.

On p.24 Mahony describes the fate of an English sculptor who sought to warm his studio in Rome with a coal-fired stove:

But concerning the development of steam-power in this capital, and the prospect for its utterly idle people of the varied branches of industry to be created through that magic medium, I can hold out none but the faintest hopes. A straw thrown up may serve for an anemometer. One of our sculptors took a fancy to import from Liverpool an Arnott stove to warm his spacious studio this winter, and laid in his stock of Sabine coal with comfortable forethought; great was his glee at the genial glow it diffused through his workshop: but short are the moments of perfect enjoyment: in a few days a general outcry arose among the neighbours: the nasal organ at Rome, guide-books describe as peculiarly sensitive : a mob of women clamoured at the gate: they were all “suffocated by the horrid carbon fossile.” Phthisis is fearfully dreaded here: with uproarious lungs they denounced him as a promoter of pulmonary disease. Police came, remonstrance was useless. The artist’s lares were ruthlessly invaded, and his “household gods shivered around him.” The Arnott Altar of Vesta now lies prostrate in his lumber yard, quenched for ever!

On p.55 the subject of gas lighting appears:

There is much of quiet amusement not untinged with a dash of melancholy supplied perpetually to strangers here by the efforts of government to arrest the progress of those modem improvements which must obviously ultimately be adopted even in Rome. The mirth which borders on sadness is stated by metaphysicians to have peculiar fascinations… Some such feelings were apt to creep o’er the mind, in reading last week the newest edict of the local authorities affixed on the walls for the guidance of all shopkeepers and others; this hatti-sheriff, which it is impossible not duly to respect, denounces the modern innovation of gas light, made of our old acquaintance, the previously denounced “carbon fossile” and all private gasworks of this nature are suppressed. Hereby many an industrious and enterprising establishment has its pipe put out all of a sudden, while those which are suffered to remain are subjected to a thousand vexatory restrictions and domiciliary visits from officials, who, as usual, must be bribed to report favourably. They are further told that their private gas generators will be all confiscated at some indetermined period when it shall please the wisdom of authority to establish government gas works: a period far remote, to be sure, but sufficiently indefinite effectively to discourage the outlay of private capitalists on their private comforts or accommodation. Milan, Florence, Leghorn, Venice, Turin, and Naples are gas-lit long since.

This really makes things clear. There is no Papal opposition to gas as such, because government gasworks are proposed. The concerns are about air-quality, and the proliferation of smog in the city from all these private burners and get-rich-quick companies. These are not illegitimate concerns, as anyone who has experienced the aroma from a neighbour’s barbeque on a swelteringly hot day can testify.

Later, on p.171, we learn that the new Pope, Pius IX, dismissed the city prefect, Marini, “an implacable foe” of “every amelioration”.

The letters, in fact, are well worth the reading, for the picture which they give of a minor Italian state, on the cusp of modern improvements in the early 19th century. Clearly the government – the Pope, if you like – did ban gas lighting, and railways, and all sorts of other modern improvements, from the papal state. This policy was reversed by Pius IX, this successor. But there is no theological question here – only politics.

It would be really interesting to see the text of the Edicts in question, actually. But I could only find one online, which was for setting up a Chamber of Commerce, here.

Papal Rome is a country which is now far away in time and space. We forget it ever existed – but it did. It was a country which had its own laws, its own army, and its own political factions. Like every Italian statelet it was perpetually concerned about foreign nations, and the threat of the Austrian army, or the French army. It is, therefore, quite a mistake to treat the political initiatives of the government of that state as if they were theological directives by a modern Pope.

Let’s return to where we started. The poster is very misleading indeed, therefore.

The first claim is mainly false. The Catholic Church did NOT oppose street lighting. The elderly ruler of the papal states in 1830s opposed gas lighting as projected by a foreign company, probably reflecting the ignorance and squalid suspicions of his people and worries about air quality. His successor ruled differently.

The second claim is mainly true, but it is entirely misleading because the reader will think of Pope Gregory as like Pope John Paul II or Pope Benedict XV. That Pope was not a modern Pope, issuing statements of faith and morals, but the autocratic ruler of a third-world state with a low-grade and corrupt administration, obstructing progress out of fear and obscurantism.

The third claim appears to be utterly unevidenced before 2015.

Thus are legends started; and, with luck, that one ends here.

All the same, I hope that you have enjoyed our visit to Papal Rome. There are indeed guidebooks online in English for visitors, which might well repay the curious reader. It may have been a backward place, but it had the charm that Rome has always had, whatever the faults of its rulers.

UPDATE: Please see the comments for further information from Italian on all this matter, and even an order by the prefect Marini, from March 1846, in the last months of the pontificate of Gregory XVI, laying down safety regulations for gas lighting.

- [1]ISBN 978-1-5144-2756-9. Preview here: “[Jesus] healed (worked) on the Sabbath and ate food consecrated to God, demonstrating the importance and power of the Spirit over the letter of the law. Back in 1831, Pope Gregory XVI opposed street lamps and banned gas lighting in Papal States. The church argued that God very clearly had established the delineation between night and day, and putting lights up after sundown flew in the face of God’s law. Still, we search the scriptures for words that would cause God to curse instead of bless us. And vice-versa. But, when did we decide to forget about God’s grace? The Church has lost much of the idealism and faith upon which it was formed and is based, replacing them instead with creeds and beliefs.” The argument is a standard among campaigners for vice. It is to be observed that such campaigners act without mercy to those who dare express any disagreement, once they have obtained power themselves.↩

- [2]So I learn from the Google search result from Bruce H. Joffe, A Hint of Homosexuality?: ‘Gay’ and Homoerotic Imagery In American Print Advertising, 2007: “Author royalties from this book will benefit the Commercial Closet Association, a non-profit 501 (c) (3) organization working to influence the world of advertising to understand, respect and include lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender…”↩

- [3]Desmond Bowen, Paul Cardinal Cullen and the Shaping of Modern Irish Catholicism, Wilfrid Laurier Univ. Press, 1983. Preview here.↩

- [4]James Whiteside, “Italy in the nineteenth century”, (1848) vol 2, p.288.↩

- [5]I owe my knowledge of this to Katarina Gephardt, The Idea of Europe in British Travel Narratives, 1789-1914, Routledge, 2016, p.112.↩

I agree and will add, that popes are allowed to say really what they like, preferably in agreement with Catholicism, but they also can speak on other matters, in this case, as a ruler of a state, he spoke about infrastructure. He was NOT speaking on anything doctrinal or anything Catholic.

It seems to me that fewer and fewer outlets of information are concerned with discovering and applying truth.

While I disagree with much of Roman Catholicism’s teachings, in my own research I consciously strive to do what you so aptly said above: “With every historical claim, our first step must be to discover whether the claim is in fact true, as stated. If it is true, we must next discover whether it is a fair representation of the facts, or a distortion.”

Thank you for your kind words. Yes, I think we must all do the same, unless we are happy to write fiction.

Some would label him an environmentalist

https://monsalvaesche.wordpress.com/2015/07/04/pope-gregory-xvi-a-19th-century-environmentalist/

I think that would be anachronistic, tho.

But I did not address in my article the frequent suggestion that Pope Gregory XVI wittily calling railways not “chemins de ferre” but “chemins d’enfer”. This appears all over the place. I find that in Yves Guyot, “L’inventeur”, (1867) p.162, the remark attributed not to the Pope but to the Archbishop of Rennes: “N’avons-nous pas entendu l’archevéque de Rennes leur lancer anathème à Sainte-Anne et les appeler les chemins d’enfer? On appelle le chemin de fer chemin d’enfer.” I can’t find anything that looks reliable to me.

“Cracked” hasn’t been good for a long, long time. All it is now is SJW clickbait.

A very nice piece of historical factchecking, as well as a blow against rejudice and hatred. Thank you.

You’re absolutely right in saying that Gregory’s decisions were based on politics and economics and they had nothing to do with theology or doctrine. Then we can argue the validity of those reasons. If they were a symptom of conservatism or were dictated by specific reasons. About the trains I can say that Gregory preferred to the trains the development of steam navigation on the Tiber and martimes links with new steamships in the Tyrrhenian and Adriatic sea something quite logical if you see the map of the Papal States and among other things a decision that does not obliged the Papal States to agreements with foreign companies. Obviously if someone is against the trains for conservatism it should be the same for steam! I read also about his worries on the security of the trains. Whas he right on this? I can only say that continuous brake and block system for trains were invented only in the 1850s.

A note on lighting gas. It is again a decision that had nothing to do with doctrine as evidenced by the fact that in the last year of his reign, 1846, he had given orders to prepare a contract for the construction of a gasometer outside the walls of Rome so that already in the 1847 we have a contract for the provision of public gas lighting in the city. Of course a decision taken late but if there were theological reasons against gas lightining this decision would never have been!

Dear @domics – this is very interesting – thank you. You are clearly better informed than I about Gregory’s policies. So may I ask what sources you use for the following claims:

* That Gregory preferred steam navigation to railways.

* That Gregory was worried about the safety of train travel.

* That Gregory XVI gave orders in 1846 to prepare a contract for the construction of a gasometer?

It’s always necessary to tie these things down to primary sources.

Thank you @Zimriel and @Suburbanbanshee.

I’m not a Catholic, but nobody is served by misrepresentations of this sort. Whatever our views, let them be based on an accurate picture of the raw data.

This story would certainly have legs, if not nipped in the bud. I could easily see that it would next appear as “Church opposed street lighting”, losing the word “Catholic”. For I notice that much atheist invective consists of anti-Catholic material from a century or two ago, edited into a jeer at the whole Christian world. This story would quickly get the same treatment.

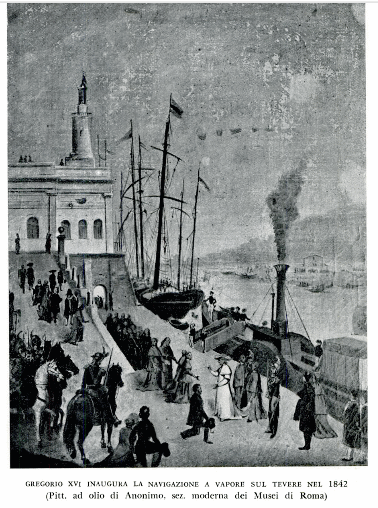

Ok, but sorry only in Italian.

On steam navigation you can see this picture, “Gregorio XVI inaugura la navigazione a vapore sul Tevere” (Gregory XVI inaugurating steam navigation on the Tiber) in P. Dalla Torre, “L’opera riformatrice ed amminstrativa di Gregorio XVI”, in: C. Lefebvre, Gregorio XVI: Miscellanea Commemorativa II, Roma: Pontificia Universita Gregoriana, 1948, p.29-121; p. 80. (Series: Miscellanea Historiae Pontificae 14).

Or this quote from Maria Margarita Segarra Lagunes, Il Tevere e Roma: Storia di una simbiosi, Roma: Gangemi Editore, n.d., ISBN 88-492-5621-5, p.357: “…è nel 1842, sotto il pontificato di Gregorio XVI, che viene definitivamente introdotto il servizio di rimorchio a vapore, gestito direttamente dallo Stato e comprendente tre piroscafi.” (… and in 1842, in the pontificate of Gregory XVI, that the steam haulage service was definitively introduced, managed directly by the state and comprised of three steamers)

It is Moroni in his “Dizionario di erudizione storico-ecclesiastica da S. Pietro sino ai nostri giorni” vol. LXX, p. 159 who lists train accidents as one of the reasons why Gregory preferred steam navigation.

On the first uses of gas in Rome during Gregory’s reign: Capitolium, Volume 29, 1954, p.55: “Il primo esperimento di illuminazione a gas fu fatto nel 1845, nel mese di maggio, nella piazza San Marco, con tre fanali.” (The first experiment with gas lighting was made in 1845, in May, in the Piazza San Marco, with three lamps.) http://tinyurl.com/zm9tvl9

On the gasometer I have a reference to an archive so it is not available on line but this first experiment in Rome confirms the point.

NOTE (RP): I have added bibliographic references to this most useful comment, in case the links rot, slight reformatting, and translations.

Here is a fuller quote from Lagunes: “Il 30 settembre 1829 approda a Ripa grande il primo batello a vapore, che effettua il servizio fino al mese di dicembre, «coll’assistenza dei rappresentanti il superiore governo e pratici della navigazione del Tevere», ma, nel seguito, l’impresa avviata dal Nizzica sembra sfumare: soltanto sei anni dopo troviamo di nuovo la Camera Apostolica impegnata nella stipula di un altro contratto per il tiro delle barche con i bufali a favore di Felice e Francesco Cartoni, mentre è nel 1842, sotto il pontificato di Gregorio XVI, che viene definitivamente introdotto il servizio di rimorchio a vapore, gestito direttamente dallo Stato e comprendente tre piroscafi. È l’inizio di una nuova era.” – “On September 30, 1829 the first steam boat station appears at Ripa grande, which provides a service until December, “with the assistance of senior representatives of the government and practical navigation of the Tiber,” but, in the following year, the company launched by Nizzica seems to fade: only six years later we again find the Apostolic Chamber engaged in the signing of another contract for hauling boats with buffalo with Felix and Francesco Cartoni, while in 1842, under Pope Gregory XVI, there is finally introduced the steam towing service, managed directly by the State and comprising three steamers. It is the beginning of a new era.” Lagunes also prints the same picture of Gregory inaugurating the steam service.

Thank you – these are invaluable. I’d appreciate the offline reference for the gasometer, even if we can’t access it.

Reminds me a bit of this howler: http://liberlocorumcommunium.blogspot.com/2016/07/an-age-old-prejudice-last-acceptable-one.html.

That’s a very nice, and crushing, demolition of that particular canard.

I wonder whether those who circulate it, jeering (as they suppose) at people in olden times for sharing the stupidity of the age, ever reflect that their only ground for objection is that they are here parroting opinions which were invented a couple of decades ago by people whom they do not know, which were promoted by reiteration and intimidation rather than rational argument, and will certainly disappear as soon as the times change?

Searching books.google.it, I find a little more:

Giuseppe Pasolini, Memorie raccolte da suo figlio, 1881, p.215: “e benche Gregorio XVI con maggior sottigliezza che buon senno le avesse sempre rifiutate dicendo: « Chemin de fer, chemin d’enfer; » il Governo di Pio IX si acconciava a permetterle.” (and while Gregory XVI with greater subtlety than sense had always refused, saying “Chemin de fer, chemin d’enfer;”, the government of Pius IX agreed to allow it.”

Italian Wikipedia contains the following remarks:

This is the image from the book:

subject: St. Nikolaos

Dear Mr. Pearse, May bee this could be interesting for you:

British Museum, Cotton Tib. B V, Fol. 57 und 58 enthält zwei Fragmente der Legende von St. Nikolaus. Das erste spielt zur Wandalenzeit in Afrika, wo St. Nikolaus seitdem sehr verehrt werde.

yours sincerly Dr. J. Schmidt

Thank you for the tip!

Here we can find prefect Marini’s regulation on gas lightining dated March 1846:

“Provvidenze sulla illuminazione a gas introdottasi in qualche abitazione, ed altra località della capitale con gassoj eretti nell’interno dell’abitato.”

http://tinyurl.com/j8bfuvp

As we can read there is no mention of prohibitions but only an imposition of appropriate security measures.

To notice point 7: “qualora al governo piacesse di permettere la erezione di un gassojo generale fuori dalle mura…”

This is really marvellous!!! An order by Marini from 1846!! Thank you so much!!

The reference is Raccolta delle leggi e disposizioni di pubblica amministrazione nello stato pontificio, Volume 23 (1849), p.161 f.

Here is the OCR of Marini’s order, “Regulations on illumination by gas introduced into some houses, and other locations in the capital, and gas installations erected inside houses. 28 March, 1846” (Gregory XVI died in June 1846).

The regulations are concerned with safety, with inspection of existing installations (which are to be permitted), and so forth, and a recognition that coal (“carbon fossile”) is the main source for the gas. A google translation will give the idea. Here is my attempt at the introduction:

Here’s the Italian:

Tangentially, the pair of alternative futuristic/science-fiction novels by Robert Hugh Benson, Lord of the World (1907) and The Dawn of All (1911) give various, interesting imaginations of late-twentieth-century Rome.