In 1999 two journalists named Timothy Freke and Peter Gandy published a book called The Jesus Mysteries: Was the “original Jesus” a pagan god? The book appealed to a “new atheist” demographic, and material from it could be found online throughout the 2000’s.

On p.49 they made the following claim, in the middle of a series of claims about similarities between Mithras and Jesus:

An inscription reads: He who will not eat of my body and drink of my blood, so that he will be made one with me and I with him, the same shall not know salvation.[183]

The footnotes reads “Godwin J. (1981), 28”. Freke and Gandy liked this so much that they repeated it in abbreviated form on the first page of their book.

The claim is actually false. In 2007 in a now defunct message forum, the question was explored. Dr Andrew Criddle did most of the work, and posted his findings.[1] I wrote up a page of notes which somehow vanished from the web. I have restored it here, but it’s rather dense, and disappears into various rabbit holes. So let’s go through the key points.

Godwin

Our first port of call is the reference, which turns out to J. Godwin, Mystery Religions of the Ancient World, 1981. It seems that Freke and Gandy did not trouble to read carefully, for Godwin’s words are:

A Persian Mithraic text, amazingly reminiscent of Jesus’s words, states that ‘he who will not eat of my body and drink of my blood, so that he will be made one with me and I with him, the same shall not know salvation.’

But there is no footnote.

The Actual Source – Vermaseren

The actual source is a publication by the Mithraic scholar, M. Vermaseren, The Secret God, London (1963). On p.103-4 appears the following claim:

Justin records that on the occasion of the meal the participants used certain formulae (μετ’ ἐπιλόγων τινῶν) comparable with the ritual of the Eucharist, and in this connection mention may be made of a medieval text, published by Cumont, in which of Christ is set beside the sayings of Zarathushtra. The Zardasht speaks to his pupils in these words: ‘He who will not eat of my body and drink of my blood, so that he will be made one with me and I with him, the same shall not know salvation….’ Compare this with Christ’s words to his disciples: ‘He who eats of my body and drinks of my blood shall have eternal life.’ In this important Persian text lies the source of the conflict between the Christians and their opponents, and though of later date it seems to confirm Justin’s assertion.

There is no footnote.

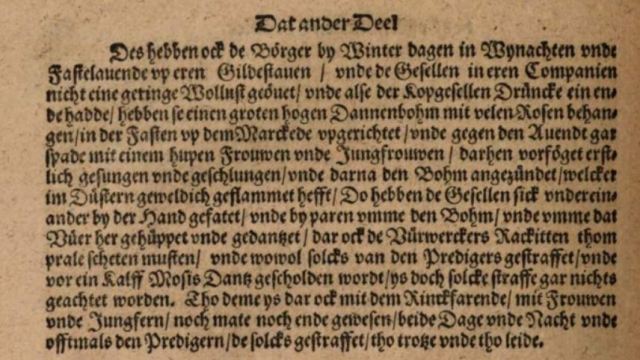

This is a poor English translation of the original Dutch text, a popular paperback, Mithras de geheimzinnige god, Elsevier (1959), which on pp.82-3 reads:

Justinus vermeldt dat de maaltijd gepaard ging met enige formules (met’ epilogoon tinon).” Ook deze kunnen veel gelijkenis vertoond hebben met die van het Avondmaal. Een middeleeuwse tekst, welke door Cumont werd gepubliceerd, is in dit verband bijzonder interessant. Want hierin wordt de waarheid van Christus gesteld tegenover het woord van Zarathustra; deze Zardasht sprak nog tot zijn leerlingen: ‘Wie niet van mijn lichaam zal eten en van mijn bloed zal drinken, zodat hij zich met mij vermengt en ik mij met hem vermeng, die zal het heil niet hebben…’. Maar Christus sprak tot zijn leerlingen: ‘Wie Mijn Lichaam eet en Mijn bloed drinkt, zal het eeuwig leven hebben.’ Deze belangrijke tekst plaatst ons midden in de strijd tussen de Christenen en hun tegenstanders en kan, hoewel laat in datum, misschien de bewering van Justinus bevestigen.

Note how the original Dutch speaks of “this Zardasht” (“deze Zardasht”), where the English translation reads “the Zardasht”, which makes it sound like a book, perhaps the Zardusht-nama; and “this important text” (“Deze belangrijke tekst”), not “this important Persian text”. There are other errors to mislead the reader.

The Cumont Article

Andrew Criddle discovered that the unnamed article used by Vermaseren was F. Cumont, “Un Bas-Relief Mithriaque du Louvre”, Revue Archeologique 25 (1946), 183-195. At the end, on p.193-5, he refers to an Arabic manuscript in Syriac characters (Garshuni) in the Mingana collection in Birmingham:[2]

Un passage étrange d’une œuvre tardive vient peut-être suppléer à la réticence de Justin, qui s’est fait scrupule de reproduire les formules païennes. Un manuscrit arabe en caractères syriaques (karshounî) de la Bibliothèque de Birmingham [3] contient une homélie ou une lettre pastorale, dont le thème est de mettre en parallèle les prétentions fausses des Juifs et des Mages et la puissance véritable du christianisme. Le motif qui y est reproduit avec une rigueur monotone est que le démon a fait accomplir aux infidèles une série de prodiges, mais qu’à ces faux miracles, Dieu en a opposé de vrais.

Venait à parler des Mages, l’auteur inconnu assure que Zoroastre ayant fondé des pyrées, exhorta ses sectateurs à se jeter dans le feu, et qu’ils semblèrent y périr dans les flammes; puis qu’en étant sortis sains et saufs, ils parurent ressusciter, mais ce n’était là qu’une illusion produite par des sortilèges. Or le Christ se mesura avec Zoroastre et, en ressuscitant réellement les morts, rendit vaine la propagande des Mages dans le monde entier.

Puis l’écrivain chrétien ajoute : « Ce Zardasht dit encore à ses disciples : Qui ne mangera pas de mon corps et ne boira pas de mon sang, de manière qu’il se mélange à moi et que je me mélange à lui, celui-là n’aura pas le salut… Mais le Christ dit à ses disciples : Qui « mange mon corps et boit mon sang, aura la vie éternelle. »

3. A. Mingana, Catalogue of the Mingana collection of manuscripts (Birmingham. Selley Oak colleges library) Cambridge. 1933. Ms. Mingana, n° 142, ff. 48 à 61. — Notre attention a été attirée sur ce manuscrit par le Père Vosté, dont l’érudition d’orientaliste nous a une fois de plus fait profiter de ses découvertes. Notre ami M. Levi délia Vida a bien voulu se charger de traduire pour nous, avec sa compétence éprouvée, l’ouvrage Karsunî qui nous intéressait, et qu’il s’est réservé d’étudier plus en détail au point de vue de ses sources et de sa date. La guerre a malheureusement interrompu ses recherches ; provisoirement, espérons-le.

1. Nous reproduisons ici la traduction de ce que dit des Mages cette œuvre difficilement accessible, et parfois peu compréhensible ; F. 158 b : …

In English:

A strange passage in a late work may perhaps compensate for the reticence of Justin, who scrupled to reproduce the pagan formulae. An Arab manuscript in Syriac characters (Karshuni) of the Library of Birmingham [3] containing a homily or pastoral letter, the theme of which is to put side by side the false pretentions of the Jews and Magians and the true wisdom of Christianity. The motif which is repeated with monotonous rigour, is that the devil has accomplished a series of miracles among the unbelievers, but, to these false miracles, God has opposed true ones.

Speaking about the Magi, the unknown author asserts that Zoroaster, having built pyres, exhorted his followers to throw themselves into the fire, and that they would seem to perish in the flames; and then coming out safe and well, they would appear to have come back from the dead, but this was only an illusion produced by magic spells. But Christ measured himself against Zoroaster, and by really bringing people back from the dead, made the propaganda of the Magi in the whole world pointless.

Then the Christian writer adds: “This Zardasht again says to his disciples: whoever does not eat of my body and does not drink of my blood, so that he mixes with me and I mix with him, he will not have salvation… But Christ says to his disciples: Whoever eats my body and drinks my blood will have eternal life.“

3. A. Mingana, Catalogue of the Mingana collection of manuscripts (Birmingham, Selley Oak colleges library) Cambridge, 1933. Ms. Mingana, n° 142, ff. 48 – 61. — Our attention was drawn to this manuscript by Fr. Vosé, whose erudition as an orientalist has again allowed us to profit from his discoveries. Our friend Mr. Levi della Vida agreed to undertake to translate the Karshuni work which interested us, with his proven competence, and he proposed to study in it more detail and determine its sources and date. The war has unfortunately halted his research; let us hope, only temporarily.

I have highlighted the important bits.

The source – Ms. Mingana Syr. 142, ff.48-61

Cumont tells us nothing much about the text other than that it is a) Christian, b) written in Arabic. This is because he doesn’t know. He is reliant on Giorgio Levi della Vida for his information. In fact della Vida did send him a typewritten translation, on 6 pages, of which the first 4 pages are preserved among Cumont’s papers at the Academia Belgica in Rome. The other two pages – the interesting ones – were no doubt tucked into a book by Cumont and are now lost.

The Mingana catalogue tells us that the manuscript itself was written around 1690, but that tells us nothing about the date of the text. It also tells us that the text contains apocryphal quotations from Aristotle.

Back in 2008 I contacted the Mingana library, and obtained a copy of the text, and a translation was made for us by Martin Zammit. Here are the materials:

Since we have an English translation, we can look at it. Here is the relevant section:

As regards the sect of the Magians, we also mention to you what Zoroaster did in the days of ‘Adyūn (sic), the eighty-second king since Adam. He opened the temples of fire and made manifest miracles which attracted souls to obey him. Among his signs (he used to do the following): he used to be where the people were, so that they find themselves in the temples of fire, and those who look on think that they got burnt. All that was an act of magic. After (some) time the people were seeing that they (f. 59a) were at fault when they were in their temples, as attested in the Book of ZBHR and in other books of the Magians. Zoroaster also said this to his disciples: “Whoever does not eat my body and drink my blood, and mixes with me and I mix with him, he shall not have salvation.” When his deeds became great and his call spread throughout existence, they boiled him and drank his brew (?). Christ the Lord, the Saviour of the world, opposed them with the true resuscitation of the dead, the healing of sicknesses and diseases, the cleaning of the lepers and the evildoers, the healing of the chronically ill and the disarticulated, the expulsion of demons and the annulment of the works of Zoroaster from all existence. At the end, our Lord said to his disciples: “Whoever eats my body and drinks my blood, he shall have perpetual life.”

This is all very weird stuff. But we can certainly see that none of this has anything to do with Mithras.

The only question remaining is what on earth this quotation from “Zoroaster”, found in a medieval Arabic Christian text, actually is.

A related Cumont Article

By 1946 Franz Cumont was a very old man. In fact his last article was published posthumously, and Andrew Criddle discovered that, just like the previous article, it contains material about strange Arabic Christian texts. This illuminates what we are dealing with.

The article is F. Cumont, “The Dura Mithraeum”, in: J. R. Hinnels, Mithraic Studies 1 (1971), p.151 ff. On page 181, note 171, Cumont refers back to his 1946 article above:

171. Justin, Apol. 1.66 (cf. TMMMM 1, p.230). On this parody of the Eucharist see my article in RA 1946 pps 183f, especially 194, where I discuss a Syriac text in which certain Magi have apparently substituted the body of Zoroaster for the flesh of the bull in their sacrificial feast. The text in question is entitled The Book of the Elements (στοιχεῖα) of the World note that precisely these elements are represented in the Mithraic versions of the banquet.

I mentioned earlier that I wrote to the Academia Belgica to locate the translation by Giorgio Levi della Vida. But they also found a letter written by orientalist P. J. de Menasce to Franz Cumont. It was where he had left it, tucked inside his own offprint of the 1946 RA article. Here it is, and I’ll give a translation in a moment.

Sir,

After reading the fine article in the Revue Archaeologique which you had the great kindness to send me, for which I thank you very much, I dug out some photocopies of some Mingana manuscripts which I had made in 1938, and I found a letter of yours of 3rd December 1938 where, concerning Mingana Ms. 142, you already outlined the parallel with the famous text of Justin.

Please permit me two observations:

1. One relates to the translation (of Mr. Levi della Vida) quoted in your note 1 on page 194: with the text before me, I think that it should be translated:

“After some time, the people believed that they were resurrected, and that they were found in their houses.” The text does not say ‘house of fire’ as it says it in the phrase where the expression is, quite rightly, translated by ‘pyrée’. This signifies, I think, that, by a magical operation they were made to come back to them. However this is of no importance… No more important is the detail that numbered the folios of the manuscript 158b and 159a instead of 58b and 59a, where, for the first letter of the name of the king contemporary with Zardasht, a ‘c’ has been substituted for the ‘ (ayin).

2. The second relates to another Karshuni text of the Mingana collection, Ms. Syr. 481, which contains a parallel text which I translate for you here:

folio 225b lines 17-20: “And Zardusht the Mage says, in the Book of the Elements of the World, to his disciples: He that eats my flesh and drinks my blood remains in me and I remain in him.”

This mention of the book of “stoixeia” is more suggestive than the mysterious “z b h r” of manuscript 142, but may help explain the latter.

The Greek word passed into Syriac and into Arabic (istaqis or istuqus) and remains in the language of classical philosophy down to Avicenna. It is very interesting to see these texts of such late origin throw some light on the archaeology of Mithraic monuments and connect them to the literary tradition of Hellenised mages. I hope, this winter, to go to Rome and to have the opportunity to visit the Mithraea of which you speak in your article of the Academie des Inscriptions.

In offering you my thoughts here once again, I hope that you find here, Sir, assurance of my most profound respect.

Fr. P. J. de Menasce O. P.

I cannot read Cumont’s scribble, but the reference to “the book of elements” in Ms. Mingana 481 is clear enough.

This, then, is the source for Cumont’s vague statement in the 1971 “Dura Mithraeum” article.

The second Mingana manuscript – Ms. Syr. 481, ff. 221v-225v

From all this we learn that we have a second Mingana manuscript, containing much the same idea. Maybe this could clarify what we are dealing with?

The Mingana collection catalogue (page 890) tells us that there are various items in the manuscript, which is not dated. Ours is described as follows:

Again I contacted the Mingana collection at Birmingham University, and obtained images of the relevant pages of the manuscript. From this a transliteration and translation was kindly made by Sasha Trieger.

Here’s a short bit:

Aristotle said also in his letter to Alexander the king: Be earnest, o king, in the pursuit of the water of life. You shall not find water of life except in a Man (225v) who is to appear in the world, clothed in this world’s clothes. If you find Him, you will find the water of life with Him. He will feed you with His food from the eternal Tree of Life. Water of life will be flowing from His hands.

He said in his treatise entitled the Book of Treasures: The treasure of life is the God Adonai, who is to appear in the universe. Those in the graves will hear His voice and will rise.

Yanfus the wise said: Glory (?) to you, o thrice-blessed, who is God the eternal (?), who shall die and abolish death clearly, when He will rise after three days.

Plato the wise said: No, by Him who sent me, verily they do not know what they speak, nor what they do. By this he means the priests of the sons of Israel who deny his words cited above.

Zoroaster the Magian said to his disciples in the Book of the Elements of Science:[3] Whoever eats my flesh and drinks my blood, will remain in me and I in him.

To the Awesome Father, and to the Son who helped and assisted, and to the Holy Spirit who perfected may there be Glory now and ever and unto ages of ages, Amen.

This, no doubt, is the source for the material in Ms. Syr. 142, which, as the Mingana catalogue noted incorporates “apocryphal sayings” of Aristotle. Clearly the words of “Zoroaster” are likewise taken from a collection of apocryphal sayings, just like this one.

About Sayings of the Pagan Philosophers concerning the coming of Christ

“Sayings” literature is a very specialist interest. Some medieval Greek manuscripts that have come down to us contain collections of “sayings” of “wise men” of the past. These collections, or different ones, also exist in Syriac, Coptic and Christian Arabic. These “sayings” are known as “gnomologia” and much of the material in the past was printed in German. Both the subject name and the language of scholarship have probably ensured obscurity. The collections belong, not to the literary elite but to vulgar Greek culture. The names of the authors on each saying could be changed, or lost. The closest modern parallel is perhaps the joke book, where every saying tends to be attributed to Winston Churchill or Oscar Wilde after a while. Authenticity is of no importance compared to impact.

Now part of the proof of the Christian gospel in the middle ages was that Jewish writers predicted the coming of Christ. During this period, however, a second line of prophecy develops, from pagan philosophers. Consequently there are collections of sayings, specifically for this purpose. Sadly the “quotations” are all bogus. But naturally these find their way into contemporary literature, and this seems to be exactly what has happened here.

This is already a long post, so it would not be useful here to discuss the gnomologia much further. However there is a catalogue of unpublished Arabic Christian gnomologia in the standard handbook of Arabic Christian litterature, Georg Graf, Geschichte der christlichen arabischen Literatur, vol. 1, on pp.483-6, which I placed online and translated here. This he introduces with the following words (translation mine):

The apologetical literature of the Christian orient used the doubtful evidence of falsified statements of ancient pagan authors and invented oracular sayings to confirm the divinity of Christianity and the truth of its teaching, as was also done to an almost indeterminable extent by Greek and late antique apologists. Collections of such proofs of differing extent and with changing text also were taken into the Arabic language in theological works, where they appear both among collections of quotations and patristic citations or separately in the manuscripts.

He then lists the manuscripts that contain some of the collections. Among these is …. Ms. Mingana Syr. 481, as given above.

Graf also gives other authors who make use of these collections. Among these is John ibn Saba, The precious pearl, who also gives the Zoroaster quote. Fortunately John has been printed in the Patrologia Orientalis 16.4, with a French translation.

Here’s the relevant bit, from chapter 19

Similarly, the spirit of Saturn (Zohal) appeared to a man named Zoroaster (Zarâdacht). His doctrine has been spread for one thousand five hundred years. He sent out on a mission seventy men on whom seventy spirits coming from the spirit of Saturn had come down and who invited the people to the worship of this star. Zoroaster said to them in the hour of his death: “If you do not eat my body and do not drink my blood, you will have no part in salvation.” After his demise, his disciples did therefore boil his body and drank of this turbid fluid. He thus obtained the accomplishment of what he had said to them.

It’s the same quote, transplanted into yet another unrelated work.

Conclusion

The claim made by Freke and Gandy is false. No source ever suggested that Mithras uttered any such words.

Instead what we have is a medieval saying, falsely attributed to Zoroaster, preserved in Arabic. The saying originates from a process where “quotations” were copied, edited, and “improved”, and, in the end, created a collection of sayings of pagan philosophers apparently predicting the coming of Christ. There is no reason to attribute these words to anybody other than a too-credulous medieval Christian. They originate in the gospel, not precede it.

UPDATE: I have just discovered a review by H.-C. Puesch, in Revue de l’histoire de religions 134 (1947), 242-244 online here, in which he makes many of the same points about this “saying”. Puesch says that he received a letter from … Fr. P.J. de Menasce! De Menasce apparently told Cumont about this in 1938. He offers various corrections to the text printed by Cumont from Ms. Mingana Syr. 142, and states that the “lost Mazdaean text” referred to by Cumont was none other than the “Book of the elements” in Ms. Syr. 481.

Like this:

Like Loading...