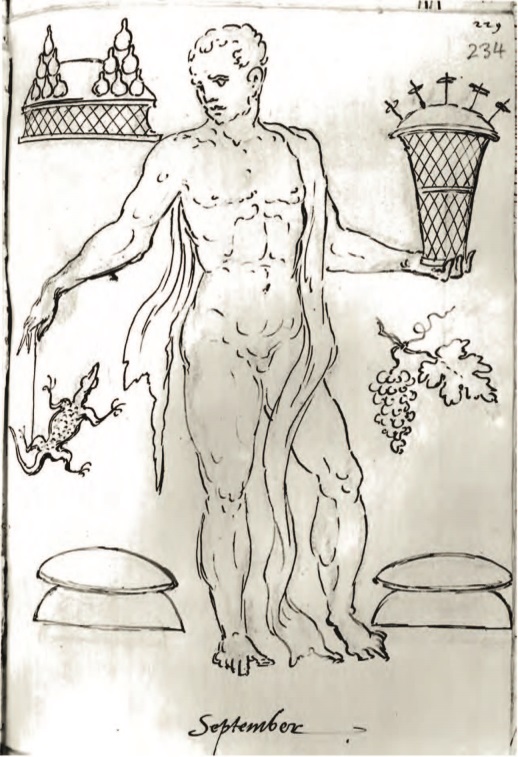

A number of manuscripts contain an image for September. But here again it is the Vatican Barberini manuscript that gives us the 4-line poem, the tetrastich:

Turgentes acinos, varias et praesecat uvas

September, sub quo mitia poma iacent.

Captivam filo gaudens religasse lacertam

Quae suspensa manu mobile ludit opus.The swelling berries and the different coloured grapes,

September cuts them down; beneath him lie the ripe fruit.

Delighted to have tied up the captive lizard with a string;

Which suspended from araisedhand plays an active game.

September 5 is Vindemia, the start of the grape harvest. The lizard can be a pest (Pliny, Natural History 30, 89), but on a thread in a container it produces medicine (NH 30, 52).

The 2-line verse (distich) is as follows:

Tempora maturis September vincta racemis

Velate e numero nosceris ipse tuo.

The season of September, coveredSeptember, temples girded with ripe grapes;

BlindfoldedConcealed, you will be recognised by your number.

I made these translations months ago, and I cannot remember if I revised them, so I apologise for any errors.

The 17th century R1 manuscript, Vatican Barberini lat.2154B (online here), fol. 20r, gives us the most accurate version of the drawing, complete with the tetrastich in the right margin, and the first line of the distich at the bottom:

The redrawn16th century Vienna manuscript 3416 (V), folio 10v (online here):

Divjak and Wischmeyer give us an image from the important (but offline) Brussels manuscript 7543-49, fol. 201r.

They also give an image from the Berlin manuscript, f.234:

From Divjak and Wischmeyer, I learn that the depiction is of the wine harvest. The cluster of grapes, the figs on a tray at the top left, and the two large amphoras / jars, set in the ground, to hold the new wine, seem clear enough. The lizard on a thread is of uncertain meaning, as is the basket with skewers on top.

(For more information on this series of posts, please see the Introduction to the Poems of the Chronography of 354).

UPDATE: Thank you Diego for correcting the distich! And to Michael Gilleland for pointing out that “suspensa” must have a short “a” and so be nominative and agree with lacerta.

The theme of the grape harvest was common, and one thinks immediately of the wonderful mosaics–dating also to the mid 4th c.–found in Santa Costanza in Rome. (https://www.wga.hu/html_m/zearly/1/4mosaics/1rome/1costanz/3vault3.html).

Oh! nice! I wish that I had a better handle on iconography…

Nice post as always.

‘tempora’ in the distich must mean the temples (of the head); ‘tempora vincta’ “temples girded with” (hedera, rosis, coronis, lauro etc.) is a common expression.

I don’t think ‘velate’ ever means “blindfolded” but just “under cover, concealed”.

Thank you so much! It’s really appreciated. I was quite unaware of the “temples” meaning for tempora, or the idiom tempora vincta. I’ve fixed the translation.

Suspensa (with short ultima) doesn’t modify manu but rather lacerta (i.e. quae sc. lacerta)..

Interesting thought. “Quae” (nominative singular feminine), referring to the “captivam lacertam” (acc sing fem) and agreeing in number and gender, but not case, and nominative as the subject of the subclause. So suspensa could agree with it, or as an ablative with manu. But if it has a short ending – I know nothing about Latin verse -, it is nominative as you say.

Could you say more about this?

If suspensa were ablative, the line wouldn’t scan. To state the obvious, it’s a hexameter. After the spondee, comes a dactyl, in which the /a/ of suspensa is the first of the unaccented, short syllables:

quāe sūs|pēnsă mă|nū || mŏbĭ|lē | lŭdĭ|t ōpus|

I appreciate you explaining the “obvious”, because I don’t know this stuff at all. Thank you. I will go and look this up.

Not “suspensa could agree with it,” but “suspensa does agree with it.” Just scan the pentameter — it’s obvious that the -a of suspensa is short, so your translation is incorrect.

Apologies for being foot-loose and fancifully free. A pentameter.

Lol. Thank you.