There is an idea that circulates in certain fringe groups in the USA that Jeremiah 10:3-5 (KJV here) condemns the use of Christmas trees. Here’s the bible passage, in the KJV (as is invariably used):

3 For the customs of the people are vain: for one cutteth a tree out of the forest, the work of the hands of the workman, with the axe. 4 They deck it with silver and with gold; they fasten it with nails and with hammers, that it move not. 5 They are upright as the palm tree, but speak not: they must needs be borne, because they cannot go. Be not afraid of them; for they cannot do evil, neither also is it in them to do good.

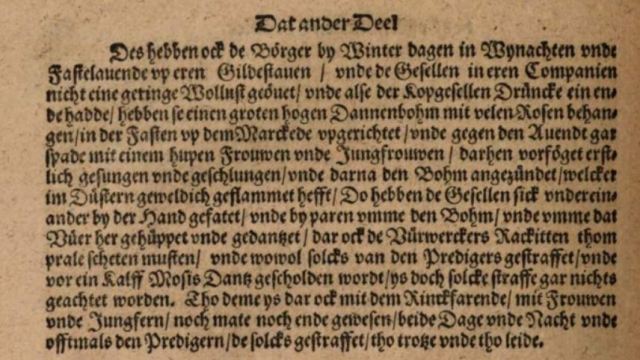

As everybody knows, Christmas – or the Nativity of the Lord – is first attested in church festivals in 336 AD, in a document, the Depositio martyrum, included in the Chronography of 354 (online here). Ancient paganism has come to an end by about 500 AD, more or less. But no ancient or medieval text records any celebration of Christmas with a tree until the end of the 15th century when it appears in Germany in a number of places. So it would be rather a surprise if it was what Jeremiah had in mind!

All the same, I thought that it would be interesting to see what ancient writers commenting on the passage have to say. I made use of the Biblindex search engine to produce a list. Here are all the results. There is a grand total of four writers who comment on the passage.

Clement of Rome (ps.), Clementine Recognitions, book 4, chapter 20. (Edition: GCS 51, 1965, p.156, l.9) Online here:

20. “And yet who can be found so senseless as to be persuaded to worship an idol, whether it be made of gold or of any other metal? To whom is it not manifest that the metal is just that which the artificer pleased? How then can the divinity be thought to be in that which would not be at all unless the artificer had pleased? Or how can they hope that future things should be declared to them by that in which there is no perception of present things? …

Cyprian, Ad Quirinum, book 3, chapter 59. Online here:

59. Of the idols which the Gentiles think to be gods.

…. Also in the 134th Psalm: “The idols of the nations are silver and gold, the work of men’s hands. They have a mouth, and speak not; they have eyes, and see not; they have ears, and hear not; and neither is there any breath in their mouth. Let them who make them become like unto them, and all those who trust in them.” Also in the ninety-fifth Psalm: “All the gods of the nations are demons, but the Lord made the heavens.” Also in Exodus: “Ye shall not make unto yourselves gods of silver nor of gold.” And again: “Thou shalt not make to thyself an idol, nor the likeness of any thing.” Also in Jeremiah: “Thus saith the Lord, Walk not according to the ways of the heathen; for they fear those things in their own persons, because the lawful things of the heathen are vain. Wood cut out from the forest is made. the work of the carpenter, and melted silver and gold are beautifully arranged: they strengthen them with hammers and nails, and they shall not be moved, for they are fixed. The silver is brought from Tharsis, the gold comes from Moab. All things are the works of the artificers; they will clothe it with blue and purple; lifting them, they will carry them, because they will not go forward. Be not afraid of them, because they do no evil, neither is there good in them. ….” 677

677 Jer. x. 2-5, 9, 11, ii. 12,13, 19, 20, 27.

Eusebius, Commentary on Isaiah, on 44:12-20. (Edition GCS, p.285 l.30). From Armstrong translation (IVP 2013), p.233:

[44:12-20] Why, then, did you never reason among yourselves and ask what is the nature of those “godmakers” who fashion inanimate statues for you? For is it not plain for all to see that the gods are the works of “artisans”?11 They have been fabricated with axes and augurs and such tools. They are the contrivances of poor day laborers, who, because of their need for food in order to pursue their work, promote the business of idolatry for the bread of leisure. And why did you not ask what is the nature of God, and whether God needs food, and whether he will become hungry if you do not offer sacrifices, and whether [286] God will also become weak if he is not nourished, or according to Symmachus: He will become hungry and weak and exhausted, and he will not drink water. And why does he say he will not drink water, unless he had actually been in need of water? And if he will neither eat nor drink, is he not in fact worse off than an irrational animal:’ How, then, have you been deceived, O vain people, when such a state of reality proves the impotence of the statues?

11. Cf. Hos 13:2;Jer 10:3.

I have already discussed Jerome, In Hieremiam prophetam libri V, book 2, c. 85-6, here.

Biblindex also gives a reference as Theodoret, Interpretatio in Jeremiam – I have no access to the English translation – text found in PG 81, column 565. But a quick look will show that he only discusses Jeremiah 10:2 and then 10:7.

Those are all the ancient writers who discuss this passage. As may easily be seen, all of them think it’s about idols. Not one thinks that the worship of a tree is involved.

The claim that the Christmas tree is pagan is often made by people familiar with Alexander Hislop, The Two Babylons: The Papal Worship Proved to be the Worship of Nimrod and his Wife (1853), a farrago of assertion and misinformation heaped up willy-nilly. The claim may be found on p.139 of this 1862 edition here. This volume still exerts an unholy fascination in some parts of US Protestantism. But the link with Jeremiah 10 only appears in the 20th century, or so it seems from a Google search, and is closely identified with Herbert W. Armstrong and those movements derived from his Worldwide Church of God such as the Hebrew Roots movement.

Unfortunately it is completely false. As a reading in context will show, the Bible is talking about the manufacture of a wooden idol.

Correction: an earlier version of this article asserted that the link between Jeremiah 10 and the Christmas tree originates in Hislop. I am happy to correct this mistake.

Update (15 Dec 2021): I have since come across an extremely good article on a Seventh Day Adventist website, here, which I will quote in slightly abbreviated form, for the benefit of those who still wonder about Jeremiah 10:

I am a Seventh-day Adventist… According to Jeremiah 10:1—5, we are told to “learn not the way of the heathen” [KJV], by bringing evergreens into our homes and “deck” them with silver and gold. … God was wroth with the Israelites when, after fashioning the golden calf, they proclaimed, “We shall make a feast unto the Lord”! Since when do we as God’s children offer Him pagan feasts?

I believe we need to ask seriously whether Jeremiah was describing the Christmas tree or something like it in the passage you quoted. First, notice that though you have identified the wood brought into the home as an evergreen, the Bible text does not do so. It merely refers to a tree.

Second, what then is done with the tree? Are silver and gold hung on its branches? The New American Standard Bible (NASB)—a conservative and quite literal translation—renders verse 3 this way: “The customs of the peoples are delusion; Because it is wood cut from the forest, The work of the hands of a craftsman with a cutting tool.” It doesn’t take a craftsman to cut down a tree. Even I can do that! So why a “craftsman”?

I believe the reason is that after felling the tree, the craftsman carved it into an idol, which the people then decked with silver and gold. This carving of an idol—not the mere cutting down of the tree—required a craftsman’s work. Verse 5 actually makes this quite explicit. Again I’ll quote from the NASB:

Like a scarecrow in a cucumber field are they,

And they cannot speak;

They must be carried,

Because they cannot walk! Do not fear them,

For they can do no harm,

Nor can they do any good.This is describing an image, a representation of a god, and comparing it to a scarecrow, something that you shouldn’t be afraid of! Isaiah 44:9-17 presents a parallel picture, but with more of the detail.

Despite the superficial similarities, Jeremiah 10 is not describing a Christmas tree nor what people do with a Christmas tree. I have seen people in a Catholic church genuflect before the images and before the altar as an act of respect and worship. But I have never seen anyone offer any such homage to a Christmas tree, and probably you haven’t either. So having a Christmas tree in the church is not an issue of false worship.

Indeed not.